- Published on

Why Modern Software Supply Chains Break Security Teams

- Authors

- Name

- Larkins Carvalho

In this industry, the only thing more predictable than a holiday is a software supply chain meltdown right before it.

I have been fascinated by software supply chain security since the start of my career. Early on, I worked on open source projects where we submitted code via mailing lists (literal patch files sent to maintainers who would review and merge them!!!). Looking back, I wonder what security assurance actually happened on code supposedly submitted by engineers working within organizations. There was trust, some code review, but mostly just faith in the community.

Long before we tried using CVE/advisory-based security, we kept component manifests (license BOMs) to evaluate copyleft licenses and the legal risk they posed. One of my intern projects involved running source code analysis to detect copyleft-licensed code or snippets "borrowed" from external sources that could expose us to liability. Security wasn't even the primary concern, it was legal exposure.

The 90% Problem

A lot has changed since then and the supply chain security landscape is dramatically transformed. We don't ship a single binary anymore. The vast majority of modern codebases consist of open-source components. The same goes for the services and vendor tooling we depend on. This means that even if we're not manually pulling in dependencies, we're still liable when something in our stack gets compromised.

Shared Responsibility as a Liability Shield

Oh hell.. the whole cloud shared responsibility model has fundamentally shifted accountability. When a vulnerability like Log4Shell emerges in a managed service or critical dependency you rely on, the burden falls on you to validate impact and patch immediately. The vendor provides the infrastructure and you own the consequences. This problem intensifies when vendors aren't security-obsessed. Many don't prioritize immediate patching. Worse, there's an escape hatch that's become increasingly common: labeling software as end-of-life (EOL). Once a product reaches EOL, vendors can wash their hands of it entirely. No improvements, no bug fixes and critically, no security updates. You're left running vulnerable software with no path forward except costly migration or accepting the risk. EOL has become the ultimate liability shield for vendors, transferring all risk to customers while they move on to the next product cycle.

The Exploitation Accelerant

Things are accelerating in dangerous ways with the rise of AI adoption, fundamentally changing the economics of vulnerability research. What once required skilled security researchers spending weeks analyzing code can now be done in hours with AI-assisted tools. Finding vulnerabilities in open-source components has become cost-efficient at scale. Even more concerning, AI is lowering the barrier to exploit development. Attackers can now generate working exploits faster than defenders can patch. The time between disclosure and exploitation - our window to respond is shrinking.

Let’s walk through the evolution of vendor solutions and discuss what organizations should actually be evaluating. Yeah, each organization's needs differ however, there are baseline expectations we can define and areas where genuine innovation has occurred versus security theater. My goal is to define baselines expectations and where we should innovate. I’ll refrain from mentioning vendor names but if you have been following supply chain / application security, you’ll know which companies I’m referring to.

The Developer-Centric Mirage

The first wave of tools brought clean UX, developer-centric APIs, and comprehensive dependency databases with rich metadata. But even with bells and whistles, the fundamental problem still existed: flagging CVEs in your dependencies is largely useless for security. It helps with compliance audits, sure, but it tells you nothing about your actual security posture. These tools can't tell you if your system is actually vulnerable. They don't help with prioritization. Not all "critical" severity issues are created equal, and depending on your operating environment, you might reasonably ignore many of them entirely. To be exploitable, you need to be using a vulnerable API from the dependency in a way that can be influenced by an attacker. The payload can come from anywhere: an external system, user input, a supply chain compromise. Without understanding your code's actual usage patterns, CVE lists are just noise.

Another claim was remediation to help accelerate fixing vulnerabilities. Here's my spicy take on remediation: vendors love claiming they are "developer-centric" by suggesting safer versions to upgrade to. But what's the actual mechanism? If you are claiming to be developer-centric by simply analyzing changelogs and version semantics (like 3.0.1 -> 3.0.2 suggests no breaking change vs 4.0.0), you are better off calling this approach developer-sabotaging. Yes, mature organizations should have integration tests to catch breakage from upgrades. But that's a stretch assumption for most teams. If you are claiming to provide remediation, your system should, at minimum, validate suggested upgrades in a sandbox environment. Some vendors are already doing this level of assurance, but there's no standardized definition of what "remediation" actually means. We need clearer benchmarks.

There are alternate solutions from the vendors where you don't have to worry about dependencies you are pulling - vendors build libraries from the source code and distribute it through their vendor-maintained registries. This addresses the systemic risk of relying on volunteer open-source maintainers for patches and removes distribution-layer vulnerabilities from the supply chain. In some cases, these vendors sponsor or adopt abandoned projects, taking on maintenance responsibilities directly. This model shifts the trust boundary but doesn't eliminate it. You are now trusting the vendor's build and distribution process instead of the open source ecosystem's. The trade-off may be worthwhile for organizations with low risk tolerance.

The First Real Step Forward

Then arrived another layer of improvement which made a real difference: reachability analysis - the first genuine improvement that changed the conversation. Instead of listing every CVE in your dependency tree, these tools statically analyze your codebase to determine if you're actually using the vulnerable API. The noise reduction is dramatic: 70-80% in practice, cutting through the alert fatigue that made earlier tools unusable. I personally have seen this happen.

The best implementations go deeper, performing transitive analysis through your entire call stack. This is essential for Python and Node ecosystems where dependency hierarchies can go dozens of levels deep. When tools can accurately identify what's actually reachable in your code, the conversation between security and engineering teams fundamentally shifts from “fix it all” to “is this worth fixing based on real risk?”. Not all reachability implementations are equal. Some vendors only analyze first-order dependencies. Others can trace paths through complex transitive chains and even account for runtime conditions. This is where evaluation criteria matter: ask vendors to demonstrate their analysis on your actual codebase, not synthetic examples.

Reachability as Baseline, Exploitability as the Future

Reachability analysis is table stakes. Any modern supply chain security solution that doesn't provide it is already obsolete.

The next frontier is exploitability analysis. Beyond determining whether you're using a vulnerable function, these tools will assess whether a vulnerability can actually be exploited based on your system's architecture and network exposure by considering factors like: Is the vulnerable service internet-accessible? What's the attack surface? What controls sit between the vulnerability and potential attackers?

This is fundamentally more complex than reachability analysis. You're no longer just analyzing application source code. You need to understand how resources are deployed and exposed. The analysis shifts from static to dynamic, incorporating runtime context and infrastructure configuration. A few vendors are beginning to explore this space although still in their early days. I’d point out that this is distinct from EPSS scores, which predict the likelihood of exploitation in the wild based on observable attacker behavior. Exploitability analysis is specific to your environment and tells you whether your deployment can be exploited, not whether exploits exist generally.

We’ve also quietly broken our own dependency graph. AI-generated code, dynamic imports, and plugin ecosystems now introduce dependencies that no SBOM or static analyzer even sees. The modern supply chain isn’t just deep, it’s alive and ever changing. When code can generate or pull in new components at runtime, the idea of a “complete” dependency inventory starts to fall apart. If we can’t model what a system actually loads, builds, or executes in real time, every exploitability score is still just an educated guess.

OpenAI's emerging security framework takes a different approach entirely: AI-driven vulnerability discovery that prioritizes finding actually exploitable issues. Rather than flagging theoretical vulnerabilities, the system attempts to construct working exploits, proving exploitability before alerting teams. This represents a shift in the industry from detection-first to exploitation-first tooling.

If AI can demonstrate that a vulnerability is exploitable in your specific context, it eliminates the endless debates about theoretical vs. practical risk. The question isn't whether this approach will become standard, but how quickly vendors will adopt it. It’s an early sign that AI won’t just help find vulnerabilities faster, it will redefine what counts as a vulnerability worth caring about.

The vendor supply chain security model remains fundamentally reactive, relying on CVEs and advisories to flag known vulnerabilities. This two-decade-old approach needs to change. "Responsible disclosure" isn't in the best interest of nation-states or cybercriminals; they are not waiting for CVE assignments before exploiting zero-days nor are they going to report while actively exploiting vulnerabilities. We need capabilities that are designed to find security issues proactively, analyzing them when a new version is released. This seems impossible but think of something like Google’s OSS-Fuzz project which helps uncover zero days in binaries/libraries mainly due to buffer overflow/memory management issues.

Along the same lines - we need to be thinking about monitoring for outbound calls as our last defense. Egress controls still remain one of the most effective controls for the supply chain. Even if there is a compromise with egress controls you can stop the bleeding / data exfiltration. Given how freely models are deployed today, egress controls have quietly become the only control that scales with engineering velocity.

Organizational Needs, Gaps and Why We Need a Solution with Batteries Included

Let’s talk about what organizations actually need today and where current supply chain security solutions fall short. I’ll keep this scoped to application and service layers, and intentionally leave out other vectors that address different kinds of supply chain vulnerabilities.

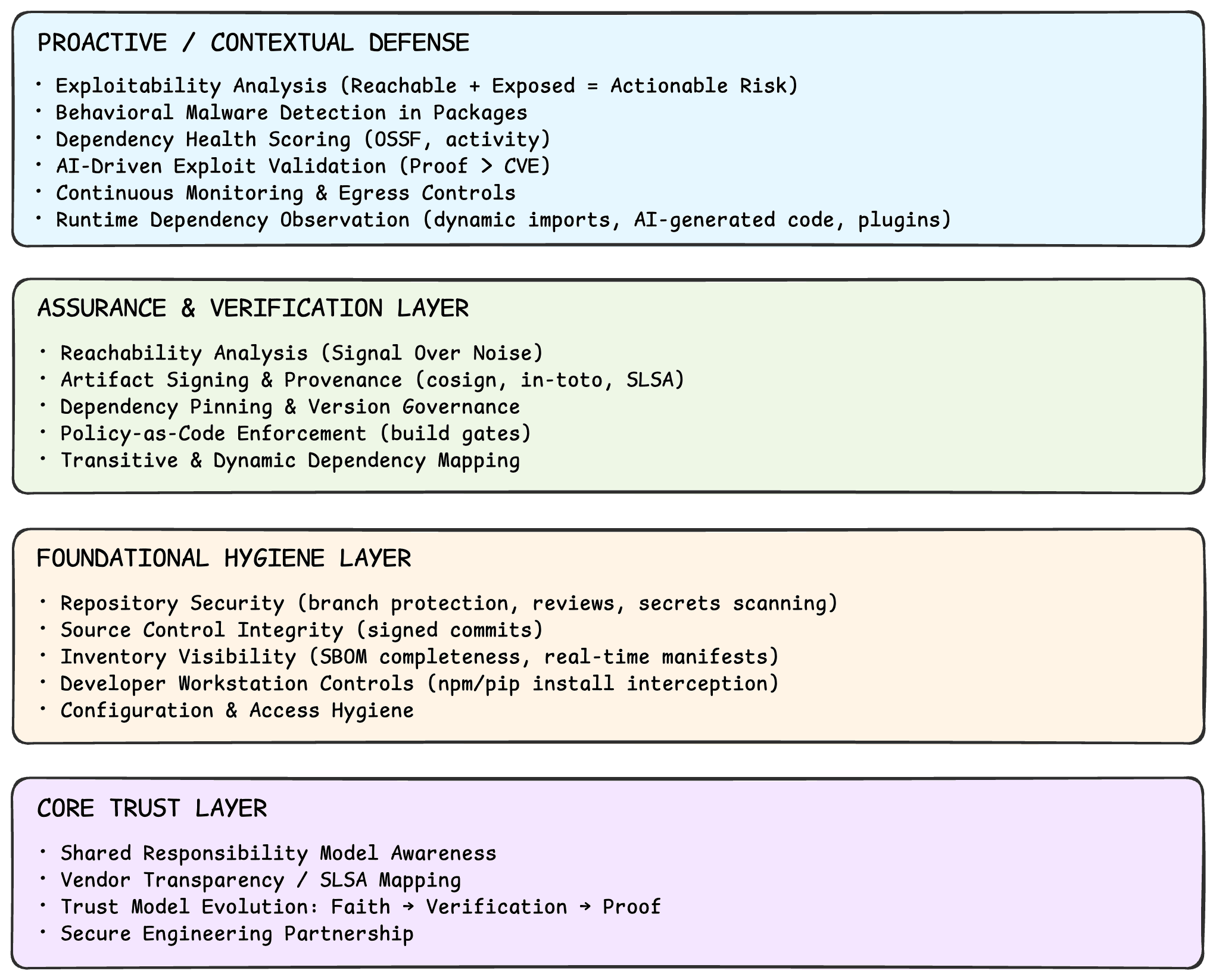

Table Stakes for Any Modern SDLC

Every forward-thinking software supply chain solution should at least cover these basics. They’re not flashy but they’re non-negotiable.

- Repository Security Configuration Analysis - Analyze branch protection rules, required reviews, secret scanning, and repository visibility settings. These are hygiene checks. Most vendors and open-source scripts can already automate them today.

- Artifact Signing and Provenance Attestation - Use tools like Cosign (Sigstore) to sign build artifacts and produce attestations that prove authenticity. Signing is now expected, it confirms integrity after the build, though it doesn’t prevent vulnerabilities or misconfigurations upstream.

- Dependency Pinning and Version Range Checks - Detect unpinned or overly broad version ranges. It’s a simple practice that prevents dependency drift, though it doesn’t address deeper risk within dependencies themselves.

- Dependency Graph Mapping (Inventory View) - Know what you pulled in directly and what came along for the ride. It gives you critical visibility but remains reactive, not predictive security.

Context, Prioritization, and Prevention

Once the basics are in place, real value comes from adding context; turning visibility into prioritization and prevention.

- Dependency Health Scoring (OSSF Indicators) - Use OSSF Scorecards, maintainer activity, project age, and governance indicators to assess dependency quality. This shifts the mindset from fixing CVEs to preventing the introduction of unhealthy dependencies.

- Behavioral Malware Detection in Packages - Detect malicious payloads, cryptominers, and credential stealers injected during install or build. This goes beyond CVE scanning, it’s behavioral and preventive, not reactive.

- Patch Management via Vendor-Patched Registries - Some vendors maintain patched or EOL versions of dependencies, reducing remediation delays. It shortens Mean Time to Remediate (MTTR) and limits business exposure while upstream maintainers catch up.

- Artifact Signing with SLSA-aligned Provenance (Advanced) - Enforce policy-driven verification, for example, only run artifacts with valid in-toto attestations. This connects build trust with runtime enforcement and moves beyond simple signing.

- Contextual Exploitability Analysis (CSPM + SDLC) - Correlate vulnerable components with cloud exposure and runtime reachability to prioritize real attack paths. This bridges application security and cloud posture, the missing link for most orgs.

- Tailored Ecosystem Guidance (PNPM Delayed Install, Pip Rules, etc.) - Offer package manager specific enforcement and feedback loops. Security guidance that matches the developer’s ecosystem makes secure choices the default.

Closing the Next Frontier

As AI and ML workloads become part of every product, new vectors emerge that traditional SCA tools don’t even see.

- Scanning ML / AI Artifacts (Models, Agents, Prompts) - Scan serialized model files (.pt, .onnx, .pkl) for malicious payloads, data poisoning, or unsafe dependencies. AI artifacts are now part of most supply chains but artifact scanning is still in its early days.

- Scanning Unconventional Files (Jupyter Notebooks) - Analyze notebook JSON for first-party code, imports, secrets, and unsafe cells. This bridges a massive visibility gap in modern data and AI workflows.

- Developer Workstation Dependency Interception - Intercept commands like npm install or pip install to scan, block, or warn before dependencies are used.

- SLSA-level Mapping for Vendor Products - Map product capabilities to SLSA Levels 1-4 so teams can benchmark maturity and integrity. Adoption is early, but transparency at this level signals real trust alignment between vendors and security teams.

Concluding Thoughts

My fellow security professionals, take a hard look at your current supply chain capabilities, and the vendors powering them. When you do, you strengthen your posture and help move the industry forward. Our ecosystem runs on vendor partnerships, and our success often reflects theirs. Treat that relationship as a collaboration, not a transaction. That’s how we raise the bar for everyone.

And to the vendors building the tools we rely on: rise to meet that standard. Strive for clarity, context, and meaningful security outcomes to build holistic solutions. Treat security teams as partners in solving real problems. Together, we push the supply chain security forward.